Hvar has been welcoming visitors for millennia. On the sailing route of both trade and pilgrimages, Hvar has always been a strategic point of interest, from modern sailing tourists to previous invading armies. Its history is as fascinating as the island itself.

As one would expect for an island, the history of Hvar has been broadly shaped and influenced by outsiders, each invading force leaving their mark, which has resulted in a rich cultural, archaeological and architectural legacy. There is much to discover for visitors interested in the heritage of Hvar, as this brief overview of the island’s history will demonstrate.

The earliest signs of civilisation on Hvar date back to Neolithic times and the so-called Hvar Culture of 3500 – 2500 BC. These estimates by archaeologists are based on artifacts and painted pottery in the caves of Grapceva and Markova Spilija, both of which can be visited today. Examples of the finds are displayed in the excellent Heritage Museum in Hvar Town.

Given its prominent position on a busy sea route, it is perhaps surprising that the island was not settled earlier than 384 BC, when the Ancient Greeks founded the settlement of Pharos (modern-day Stari Grad). The Ionian Greeks, the Parans, were in search of a base for military and trade expansion and the deep bay at Pharos offered the best protection.

The first recorded naval battle in the Adriatic took place just off Hvar, with the Greeks successfully taking on the native Illyrian tribe of the Liburni, an account of which was written by Diodorus of Sicily.

While there is some evidence of Greek heritage in present-day Stari Grad, the most striking remnant is the UNESCO-protected Stari Grad Plain, a superbly preserved 80-hectare agricultural colony still in use today.

With the decline of the Syracuse Empire, Pharos enjoyed a brief period of local rule under Demetrius of Hvar, who kept the Romans at bay until they finally smashed the walls of Pharos in 229 BC. The Romans used the island as a strategic and logistical base, keeping their boats in the protected bays of the Scedro and the Pakleni Islands. Roman holiday houses sprang up in the bays close to fresh water, most notably in Hvar, Stari Grad and Jelsa. Archaeological finds confirm that the islanders were engaged in an existence of wine growing, fishing and trade.

There is little recorded about Hvar after Roman rule but the island was under a Croatian state of the Neretljani in the early Middle Ages, along with surrounding islands, before being briefly occupied by Venice in 1147. This was only temporary, however, as Croatian-Hungarian King Bela III managed to bring Dalmatia under his rule.

The Venetians were back in 1278, having been invited back by the islanders looking for protection from the pirates of Omis. One of the early changes the Venetians introduced was to move central administration from Stari Grad to Hvar, and the new centre became a regional centre of administration for Hvar, Vis and Brac. A plan to build walls around the town and monastery was initiated in 1292.

Venice’s rule was far from secure, and the island’s noblemen rebelled in 1310, and the Hvar’s rulers changed several times (Croatian-Hungarian kingdom, Bosnian kingdom and Dubrovnik) before, along with the rest of Dalmatia, a more protracted period of Venetian rule from 1420 to 1797.

Hvar became the main Venetian port in the eastern Adriatic, but was under constant threat of attack from the Turkish fleet which controlled the mainland near Makarska. A devastating Turkish naval attack in 1571 under Algerian commander Uluz Ali in 1571 laid waste Vrboska, Stari Grad and Hvar.

Hvar prospered under Venetian rule, and was known as a place for wine, lavender, olives, rosemary, fishing and boat building. More than three centuries of rule from Venice came to an end in 1797, when the Austrians briefly took over before themselves being usurped by the French. The Russians bombarded Hvar in 1807 in a period of general instability and warfare in Europe, until the Austrians retook control in 1813, a rule that lasted into the 20th Century.

Austrian rule was stable and brought prosperity, most notably in the development of health tourism on the island, with the founding of the Hvar Hygienic Society in 1868. The oldest meteorological station in Croatia was also established in 1858. Austrian rule also brought infrastructure improvements to the island, with all the ports rebuilt, new lighthouses, malaria-infested marshland reclaimed, and a road connecting Jelsa to Pitve and Vrisnik in 1907. The old road from Jelsa to Hvar did not appear until the 1930s, and previous travel options were ship or 8-hour donkey ride.

The Italians were back in November, 1919, occupying Hvar once more after fierce fighting, an occupation which lasted until the 1921 Treaty of Rapello consigned the island to membership of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later the first Yugoslavia and then the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Hvar’s latest (and one would hope permanent) change of master occurred on January 15 1992, when Croatia was recognised as an independent state.

With the billionaire yachts moored up and the picturesque stone squares full of tourists in the numerous cafes, it is hard to imagine that the citizens of Hvar were caught up in war less than 25 years ago. A common request from incoming tourists is a simple explanation of the war in Yugoslavia, and while much has been written on the subject, rather less has been documented about the effects of the war on Hvar.

The former Yugoslav army (JNA) attacked Croatia in July 1991 and Hvar was blockaded the following month. The main effects of the blockade were shortages of foodstuffs normally brought from the mainland, such as flour, and no access to hospitals and main medical services.

After the sinking of some JNA ships from land fire on Brac and the Peljesac Peninsula, a ceasefire was signed and the navy left Sucuraj territorial waters on December 3 1991.

The situation on the ground in the mainland was dire, with large tracts of Croatia occupied. A steady stream of refugees had to be housed, and a logical supplier of beds was Hvar, devoid of tourists due to the conflict. Refugees, particularly from the front-line town of Vukovar, began to arrive by boat.

The refugee situation deteriorated in 1992 as Croatia took in numerous refugees from the brutal war in Bosnia and Hercegovina. The effect of traumatised refugees replacing affluent tourist was two-fold: severe reduction in revenue and severe increase in wear and tear in the hotels.

A UN fact-finding mission in August 1992 found that there were 624 displaced persons and 3,727 refugees on Hvar, of whom 1,323 were in private accommodation, the rest in hotels. Usually closed in winter, most of the hotels had no heating instillations, which caused problems for the new temporary residents.

Although never invaded, Hvar did experience enemy attack, and the tiny airstrip in Stari Grad was bombed at least twice. The main result of the bombing was denying local people emergency services on the mainland.

With the demographic balance upset both ways – increased population during the winter and decreased in the summer due to lack of tourists – the hotels were full all year, which had a negative impact on the condition of the buildings.

The absence of many paying visitors had a devastating effect on the island’s economy which resulted in many cafes and restaurants closing.

The cafes & restaurants closed because of the lack of electricity (because of the occupation of the Peruca dam, source of hydro-electric power) and the difficulties of obtaining necessary goods such as coffee, milk etc from the mainland. Many of Hvar’s male population were drafted into the defence forces on the front line near Zadar, where one man from Stari Grad was killed and many more returned suffering from PTSD.

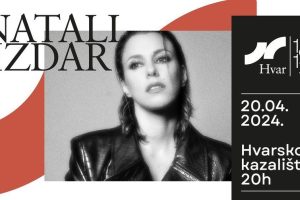

Thankfully, both Hvar and Croatia have recovered well from those dark days. A highly successful marketing campaign under the slogan, Croatia, the Mediterranean as It Once Was, proved very effective, and a new generation of tourists joined the returning older generation to discover the magic of the Adriatic. Hvar was named as one of the top 10 most beautiful islands in the world by readers of Conde Nast back in 1997, and it has never looked back. Major investments in the town’s hotels and the upgrading of cultural treasures such as the Arsenal and the oldest public theatre in Europe has meant that Hvar is once more a major luxury tourism destination on the Croatian coast.

Hvar, the cradle of Croatian tourism, celebrated 155th anniversary of tourism.

Hvar’s geographic position, its favourable climate, clear sea and rich cultural heritage favoured the development of the organised tourism in the distant 1868, when the Hvar Hygienic Society was founded. It was opening the gate to make it the most important branch of the town economy and bringing Hvar to the fame of a worldwide known tourist destination visited by most demanding and famous visitors from all over the world. The 155th anniversary of the oldest organised tourism in Europe was celebrated in some style in 2018.